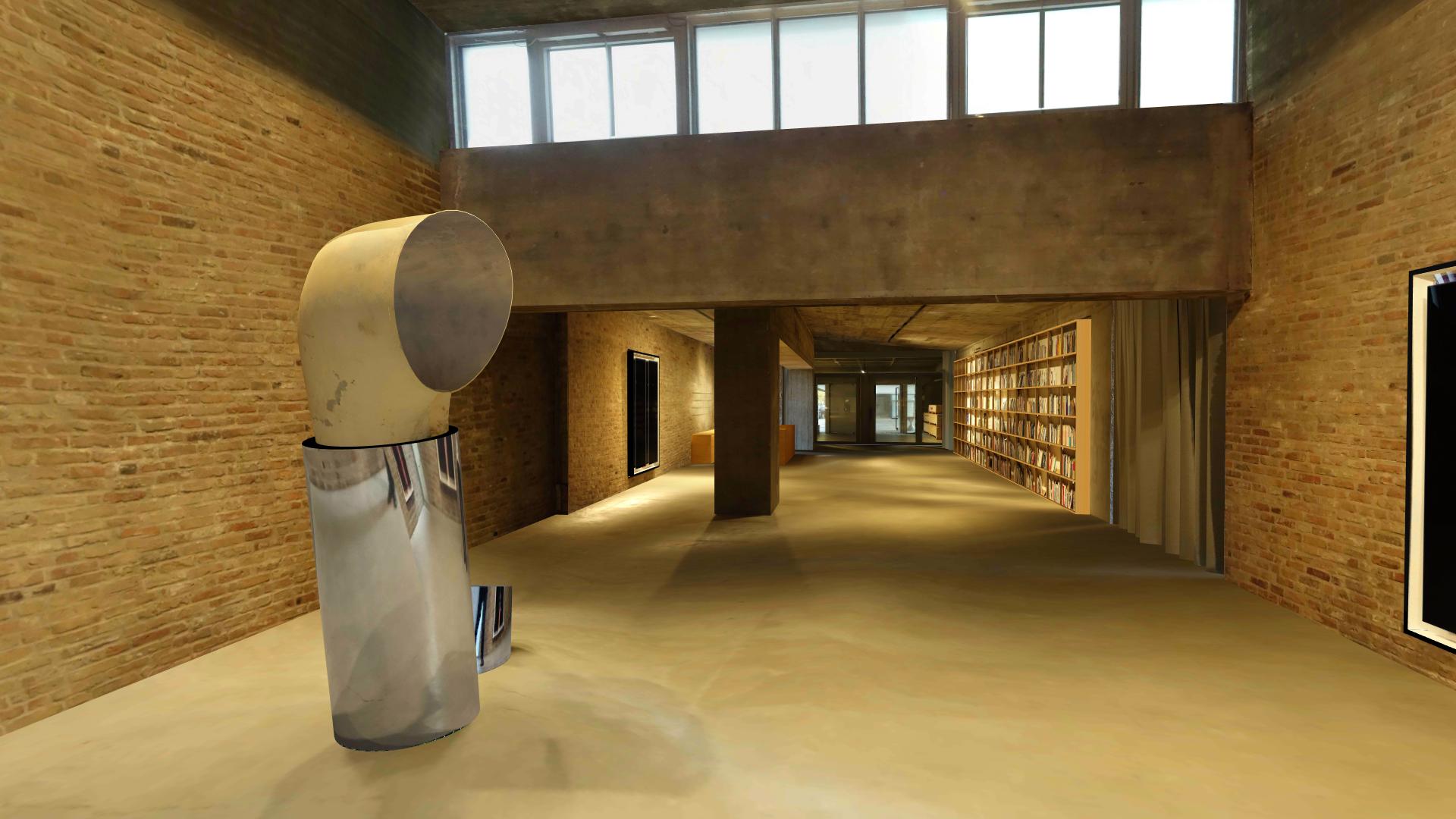

König Galerie is pleased to announce its first exhibition by Los Angeles-based artist Kathryn Andrews. Entitled Black Bars, the show will feature a group of large-scale wall-based works as well as free-standing sculpture. The exhibition will open on Friday, September 22, 2017, and remain on view through October 22.

Available:

September 22, 2017 -

October 22, 2017

About:

Kathryn Andrews’s work disrupts the way perception functions in the contemporary media-saturated landscape. She juxtaposes highly iconic forms, such as pop-inflected imagery and Hollywood props, with abstract and minimal ones that have an intense material presence. Her combines prompt viewers to w...

more >>

Kathryn Andrews’s work disrupts the way perception functions in the contemporary media-saturated landscape. She juxtaposes highly iconic forms, such as pop-inflected imagery and Hollywood props, with abstract and minimal ones that have an intense material presence. Her combines prompt viewers to waver between seeing in terms of images and illusions (a mode associated with pop art) and seeing in terms of materials and objects (a mode associated with minimalism). As such, the work moves toward resolving the apparent opposition between these two historical approaches in art. Black Bars draws its title from an ongoing series of wall-based works inspired by Manet’s landmark painting Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, in which a picnic scene is imbued with disconcerting sexual tension and jarring incongruities of scale. Andrews uses these themes as a fulcrum in order to address the deep-running connections between image and desire in the Western cultural canon. Random screen-printed assortments of objects that symbolize easy pleasure and leisure activity surround the faces of young women on a white painted ground, updating Manet’s spread with a more contemporary and at times comedic language that could be seen as reminiscent of fashion advertising. While some imagery is licensed, much is in fact produced in photo shoots arranged by the artist herself. By recreating what would otherwise pass as stock images, Andrews situates her own authorship within a system whose commercial motives are defined by conscious and unconscious expressions of desire, calling attention to ways in which the human subject can be rendered––and function––as a prop. At almost 2.5 meters tall, the works possess a monumentality further accentuated by imposing black bars screen-printed on the inside surfaces of the acrylic glass panes that separate the viewer from the images behind them. Blocking the images in their totality, the black bars deny access to the illusions of pleasure beyond, focusing attention on the immediate physical properties of the object before the viewer: the reflectivity of acrylic glass, the textures of the painted substrate within the frame, and the colors and qualities of the ink that makes up the images. Andrews’s command of printing techniques allows her to imbue two-dimensional forms with a palpable sense of weight. As the viewer moves towards the images and begins to decode them, they break down into their constituent material parts. Their content is therefore not limited to the cultural narratives they symbolize, but also includes the means by which they appeal directly to the senses. On the one hand, Andrews’s practice embodies the image-based criticality often associated with the Pictures Generation, as she demonstrates a willingness to embrace familiar representational forms. On the other hand, her work is closely aligned with several strains of minimalism in which such forms would be considered anathema. Her interest in opticality, for instance, evokes West Coast precedents set by the Light and Space artists, who also questioned how and what a viewer perceives when encountering an artwork. Over the last five years Andrews has developed a series of sculptures, featuring the use of human-scaled stainless steel tubes, in which these seemingly divergent fields of inquiry are shown to be interdependent. In the newest of these sculptures, Andrews employs two steel tubes as framing devices for a certified prop from the 1997 film Titanic. A horn-shaped vent that was part of the underwater set used to depict the sunken ship, the prop shares clear formal similarities with the steel tubes alongside which it is displayed. The three tubes can be read as parts of a single, continuous, abstract object whose effects are based on the variety of its shapes, colors, and surface textures. But the work also retains mimetic relationships to external forms on a variety of levels, including nautical imagery in general, the specifics associated with the film Titanic, and the actual history of the Titanic’s ill-fated voyage. These contradictions become only more pronounced when the viewer peers into the tube that holds the prop: if its upper portion offers some semblance of fidelity to a real vent, the prop’s lower section reveals the foam and other materials that make it no more than an example of three-dimensional trompe l’oeil. Unlike the comparative perfection of the stainless steel, the Titanic readymade shows signs of use and age. Its deterioration is a reminder that icons and images, which move through the culture as if exempt from the laws of nature, are in fact dependent upon their physical substrates, and are thus as vulnerable as the materials in and on which they appear. If such images achieve any kind of reprieve from this condition, they do so only in the minds and memories of their viewers. In 2017, Kathryn Andrews (b. 1973, Mobile, Ala.) will present her work in Field Station, a solo exhibition at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Mich. Other recent solo exhibitions include Kathryn Andrews: Run for President, Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, and Nasher Sculpture Center, Dallas; Sunbathers I & II, The High Line, New York; Temporary Contemporary, Bass Museum of Art, Miami; and Special Meat Occasional Drink, Museum Ludwig, Cologne. Recent group exhibitions include Reconstitution, LAXART, Los Angeles; 99 Cents or Less, Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit; High Anxiety: New Acquisitions, Rubell Family Collection, Miami; Progressive Praxis, de la Cruz Collection Contemporary Art Space, Miami; Good Dreams, Bad Dreams: American Mythologies, Aïshti Foundation, Beirut; The Fleeting Image: Four Contemporary Artists, Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, N. C.; and The Los Angeles Project, Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, Beijing. Andrews lives and works in Los Angeles.